Genetic Research Pinpoints a Lethal Risk Linked to Adams-Oliver Syndrome

PR Newswire

CINCINNATI, Dec. 1, 2025

Disrupted heart and vascular development traced to gene variants affecting NOTCH1 signaling

CINCINNATI, Dec. 1, 2025 /PRNewswire/ -- Scientists at Cincinnati Children's have taken a key early step in understanding why some people born with the rare disease Adams-Oliver syndrome (AOS) experience potentially fatal disruptions in heart and vascular development.

The study, published Dec. 1, 2025, in JCI, reports developing the first mouse models that accurately mimic key outcomes of the inherited condition, which affects about one in 225,000 births. These mice helped the research team identify a gene variant that is required for dangerous heart problems to appear. The team also showed that a gene editing treatment applied during early pregnancy in mice largely reversed the risk.

While gene editing remains impermissible during human fetal development, the findings also suggest that targeted post-natal treatments eventually might blunt some of the health risks linked to AOS.

The study was led by first author Alyssa Solano, an MD/PhD graduate student, and corresponding authors Brian Gebelein, PhD, and Raphael Kopan, PhD, all within the Division of Developmental Biology at Cincinnati Children's.

"We plan to use similar approaches to study whether adult mice can be treated," Gebelein says. "Addressing later-stage symptoms—such as vascular issues in wound healing as well as vessel leakiness and hemorrhages that can lead to bleeding—could still be beneficial for children and adults living with the condition."

Every year, about 40,000 babies are born with a congenital heart defect in the U.S. Only a tiny few of these children have AOS. However, the new findings may also apply to some other vascular and heart defects when they also involve NOTCH1 signaling, the co-authors say.

"It is known that NOTCH1 variants in humans more frequently cause non-syndromic heart defects than the syndromic defects associated with AOS. However, it remains unclear why some patients with NOTCH1 variants develop the additional more severe phenotypes associated with AOS," Gebelein says. "Dissecting the tissue-specific mechanisms underlying each of these defects in mice will therefore be useful to better understand the causes of NOTCH1 related diseases."

What is Adams-Oliver syndrome?

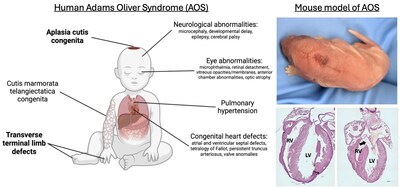

AOS is a rare congenital disorder characterized by a thinning or absence of skin and skull tissue at the top of the head, often occurring along with abnormalities affecting the hands and feet. Many born with AOS also have heart and vascular defects and some have neurological defects.

With no cure available, clinicians generally treat the major symptoms via skin grafts, surgeries to correct limb defects, and sometimes extensive surgery shortly after birth to address heart malformations.

Previous studies have established that about 40% of people with AOS have variants in one of six genes: NOTCH1, DLL4, RBPJ, EOGT, DOCK6, and ARHGAP3. The new study focuses on the RBPJ gene variants and how they drive heart and vascular malformations.

Using their new mouse models, the research team determined that the most severe disruptions occurred among mice with a gene variant called RBPJ E89G that specifically affected cells forming vascular tissue. These cells generated significantly less NOTCH1 signaling than normal.

NOTCH1 signaling plays a vital role in human fetal development. It helps manage the formation of multiple body structures, including the heart, blood vessels, the nervous system and other organs. The new study sheds light on precisely how this process gets disrupted among people with AOS.

"AOS-associated RBPJ variants do not function as loss-of-function alleles but instead act as dominant-negative proteins that sequester cofactors from DNA," the study states.

Can NOTCH1 signals be boosted?

"Prior studies have supported the idea that dysregulated NOTCH1 signaling can cause AOS pathogenesis, but it was unclear in which tissues the dysregulation occurred," Gebelein says. "Our mouse study demonstrated that dysregulated NOTCH1 signaling within only the vascular endothelium is both necessary and sufficient to drive the disease."

Removing the dysfunctional gene variant rescued mice in the study from cardiovascular complications. Attempting the same treatment approach used in the mice would require gene editing of human embryos as they develop. That's not likely to be a permissible form of treatment anytime soon.

But efforts can move forward to determine whether a small molecule or other treatments can be developed to enhance this type of weak NOTCH1 signaling after a child is born, Gebelein says.

Multi-year effort to reach a starting point

The team began its focus on RBPJ variants in studies involving Drosophila (fruit flies). They went on to develop two mouse models that mimic key aspects of AOS in humans.

"This project has been several years in the making," Gebelein says. "It began through a collaboration with Rhett Kovall's lab at the University of Cincinnati, in which we combined molecular modeling, biochemistry, and Drosophila genetics experiments to understand how mutations affect RBPJ function and dysregulate Notch signaling."

But the team needed mammalian data to move forward. Four years ago, the lab teams for Gebelein and Raphael Kopan, PhD, received internal funding from Cincinnati Children's to attempt to develop mice that can mimic AOS. They succeeded with support from the medical center's Transgenic Animal and Genome Editing Core.

What's next?

A wide range of heart defects have occurred among children born with AOS, including atrial and ventricular septal defects, valve anomalies, aortic and pulmonic stenosis, coarctation of the aorta, patent ductus arteriosus, persistent truncus arteriosus, tetralogy of Fallot, cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita (CMTC), portal vein agenesis, portal hypertension, esophageal varices, intracranial hemorrhages, and thrombosis.

Gebelein and colleagues are exploring three new lines of research:

- To develop a postnatal mouse model of AOS to determine if strengthening NOTCH1 signaling can improve postnatal vascular growth and prevent vascular defects from worsening.

- To further study why RBPJ gene variants are associated only with AOS and not another NOTCH related syndrome known as Alagille syndrome.

- To develop gene-edited pluripotent stem cells to develop organoids or other customized tests to study human blood vessel growth affected by AOS-associated RBPJ variants.

About the study

Cincinnati Children's co-authors also included Kristina Preusse, PhD, Brittany Cain, BS, Rebecca Hotz, BS, Parthav Gavini, Christopher Ahn, MS, and Hee-Woong Lim, PhD. Co-authors also included researchers at the University of Cincinnati, Xavier University, the University of London, and King's College London.

The Cincinnati Children's Transgenic Animal and Genome Editing Facility, Integrated Pathology Research Facility, Genomics Sequencing Facility, and Bio-Imaging and Analysis Facility also contributed.

Funding sources for this study include the National Institutes of Health (R01GM079428) and the National Science Foundation (2114950).

![]() View original content to download multimedia:https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/genetic-research-pinpoints-a-lethal-risk-linked-to-adams-oliver-syndrome-302629541.html

View original content to download multimedia:https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/genetic-research-pinpoints-a-lethal-risk-linked-to-adams-oliver-syndrome-302629541.html

SOURCE Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center